There was a small number of women photographers and correspondents in the Second World War, and almost all of them were with the US forces as the British Army would not allow women reporters to be accredited (the official status and rank that allowed them to move around with the armed forces).

Women reporters were only allowed to report on non-combatant stories, but Lee Miller’s second assignment at the siege of St. Malo found her unexpectedly covering a battle lasting four days. The US Army put her briefly under house arrest afterward for violating the terms of her accreditation.

Another female Second World War photographer we have photographs of is Margaret Bourke White, who mainly worked with the US Air Force. Lee Miller’s distinction was that she mainly reported the infantry war, up close and very personal.

As stated by Antony Penrose ‘George Santayna, the philosopher and poet, is credited with a saying that goes something like ‘Those who ignore history are condemned to repeat it’ and this alone constitutes a worthwhile moral and objective basis for war tourism.

When I myself visited Dachau I found the experience overwhelming, and it brought me closer to the sufferings of those who endured life in the camps and perished there. It also reminds me about the astonishing capacity man has for inhumanity to man. I was interested to see the effect the place had on others…We all react differently and take away our own experiences of these places, but at some level it goes in and stays. I hope that it leads people to an evaluation of moral issues and of the importance of fundamental values like freedom in its many forms which we tend to take for granted so easily when we have it.

The danger of war tourism is that some sites become politicized, cheapened, sensationalised, or the message within them distorted. A high degree of integrity is essential on the part of the curators. One can see much of this range in exhibits and locations around the world. The Imperial War Museum London has a devastatingly detailed and poignant holocaust exhibit, and the Imperial War Museum in Manchester is wonderfully strident in its anti-war message. Yet inevitably sometimes the armed forces museums, despite their own good intentions, end up celebrating what is seen as the glory of war. It is a fine line, one that must be treated with great discernment. No one wants to denigrate the sacrifice and commitment of the serving men and women, but these exhibits are not always seen as challenging the basic concept of why we have wars in the first place.’

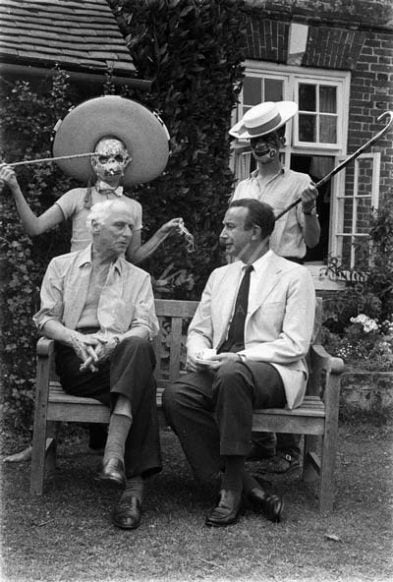

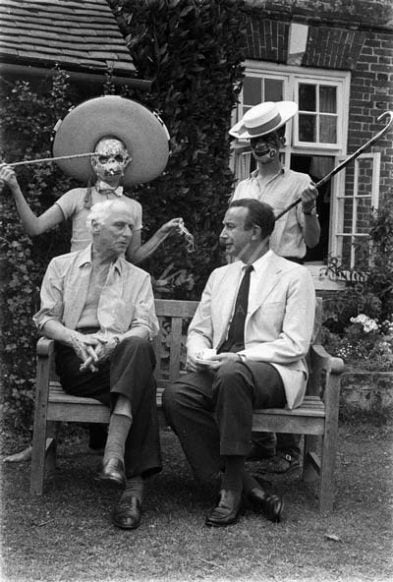

Lee had one son with Roland Penrose, Antony Penrose, born in 1947, who is the co-Founder and co-Director of the Lee Miller Archives.

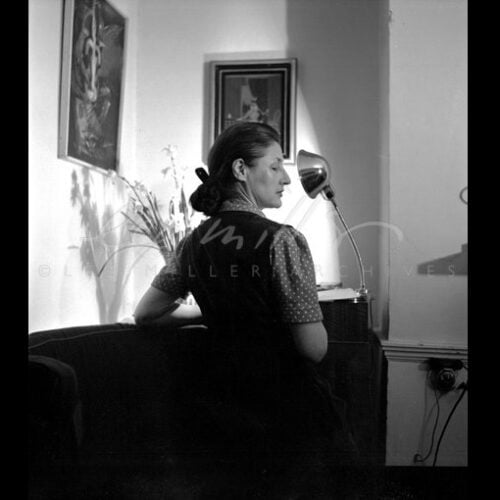

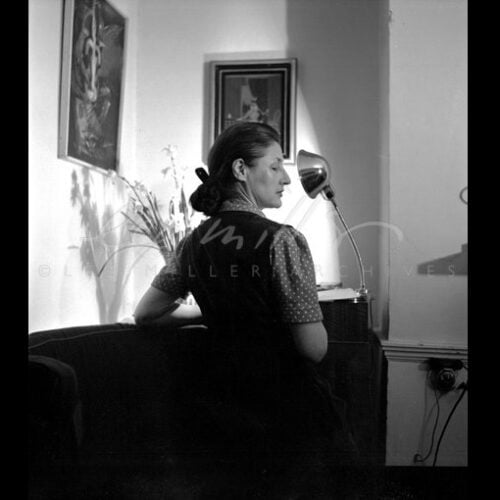

Lee Miller was born and spent her childhood in Poughkeepsie, New York USA. From 1929 she lived and worked in Paris, France returning to her native New York in 1932. She married and emigrated to Cairo, Egypt in 1934 and left to be with Roland Penrose in London, England in 1937. The pair lived in London until 1949 when they bought Farleys in East Sussex, England, and remained there for the rest of their days.

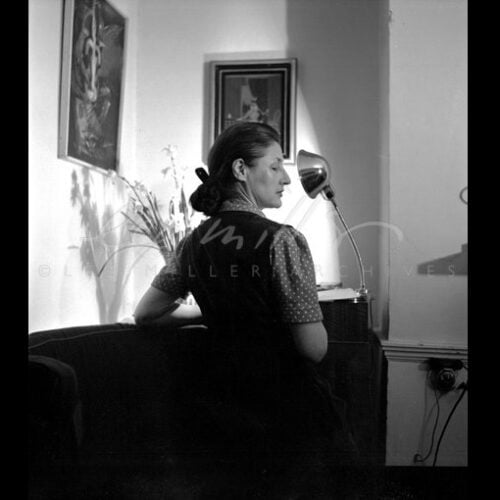

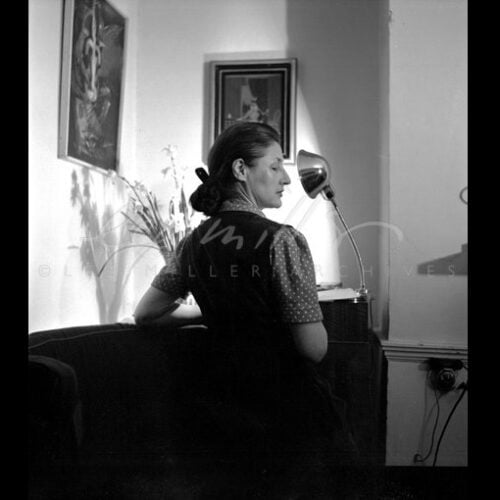

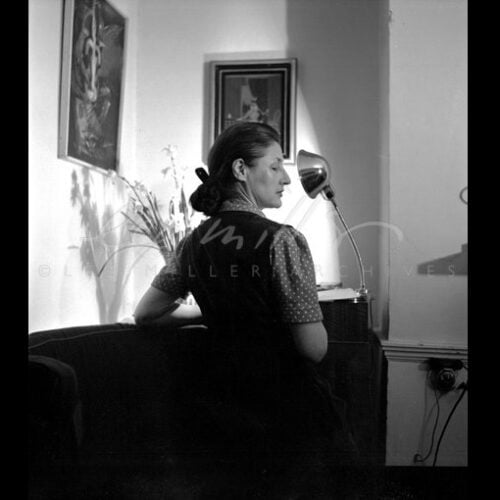

Lee Miller was an excellent photographic printer, and she learned some of her technique from Man Ray. She printed all her own work and some of Man Ray’s in her Paris days, and to begin with in her New York studio, but she trained her brother Erik Miller to be her assistant and to take over the darkroom work under her supervision.

In Egypt, she used commercial processing, but it is probable that she took a firm role in supervising the making of the enlargements she had made, some of which were published and exhibited at the time.

During the London Vogue studio days in 1940 she at first found herself back in the darkroom, but she managed to train and encourage her assistant Roland Haupt to the point where he did all the routine work. It was at this time she took a big interest in pioneering colour photography and was closely involved in the early processing work. After she went to Europe with the U.S. Army, all the processing and printing were done by Vogue studios except for a few occasions when she set up an improvised dark room in the field.

Lee Miller was cremated and her family scattered her ashes in the garden of her home at Farleys Farm, in Sussex, England. You can visit the house and garden at Farleys during our open season from April to October each year.

Lee’s son Antony has no doubt she would be very moved to find that so many people find her work intensely meaningful.

‘After all these years Lee still has the capacity to delight, provoke and inform and inspire people who take an interest in her work. Lee would probably be surprised, and very gratified by the importance attached to her work by scholars and museum curators. She would undoubtedly be pleased to see those she loved celebrated through her pictures of them.’

1. You and Roland Penrose were in Paris at the same time in the late twenties and you had several friends in common, Man Ray, the Éluards, Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, how is it you did not meet each other then?

2. When did you first meet Picasso? Was it in 1937 at Mougins or did you know him before then?

3. What happened to your negatives from your Paris studio?

4. What happened to the rest of the negatives from your New York Studio?

5. Why did you go on into Eastern Europe in 1945? What drove you, when you could have so justifiably returned to England?

6. When you were consigning your material to the series of cardboard boxes in which I found it, what was on your mind? Did part of you realise what a legacy it was and maybe it was like creating a time capsule, or was there something else?

7. If there were key defining moments in your life, what were they?

8. Would you mind reading the stuff I have written about you and telling me where I have got it wrong?

Lee Millers’ favourite camera was the German-made Rolleiflex, a twin lens reflex camera that used 120 gauge roll film and made 12 negatives 60 m/m (2 ¼ inches) square. It was very reliable and had excellent lenses.

It seems that she owned her first one between 1933 and 1935, as her first significant 60 x 60 m/m negatives date from her Egypt years. Rolleiflexes were very expensive and it is possible that Aziz Eloui Bey, her husband bought them for her.

We don know the make of camera she used when she was working with Man RAY in Paris or later in her own studio but from the negatives that remain, it appears they were mainly half plate and full plate cameras.

Her wartime colleague, the Life Magazine photographer, David E. SCHERMAN recalled that she used the big full plate studio cameras at Vogue with great ease and familiarity.

During the war years Lee MILLER also owned and used a 35 m/m Zeiss Contax camera with several interchangeable lenses, but she mainly used the Rolleiflex even on combat work.

In the post-war years she owned a Rolleicord, and then finally in the late 1960s she bought a Honeywell Pentax which delighted her with its built-in light meter and excellent coated lens.

Lee Miller used the standard printing techniques of the day utilising silver gelatine paper. Her brother Erik recalled;

‘We always used to plunge right in, rubbing the surface of the print and blowing on it so the warmth would enhance the tone in a specific area. We had a vast array of chemicals which we used to dose up the normal proprietary solutions, and the resulting brew sometimes became quite deadly. We would cough and splutter in the fumes, and my fingernails would turn brown. Looking back on it, if there had been such a thing as safety inspectors in those days we would have been out of a job.’

(Erik Miller in conversation with Antony Penrose, July 1974. Quoted in The Lives of Lee Miller by Antony Penrose, Thames and Hudson England 1985, p. 45).

The process of Solarisation, also known as the Sabatier effect was first noted in 1862 by Armand Sabatier, a French doctor and scientist, who described it as pseudo-solarisation reversal. It was more commonly known as the Sabatier Effect, but its usage was limited to experimental production of positives from original negatives.

The effect is produced by the extreme over-exposure of the negative during a critical stage of development. The shadow areas are the most affected, developing to a greater density than the original negative image. The characteristic reverse halation line that forms on boundaries between adjacent highlight and shadow areas is sometimes known as the Mackie Line. The increased concentration of bromide along these boundaries greatly retards the development process, forming a clear rim in the negative that prints as a black outline.

It is not known how familiar Man Ray was with the work of Sabatier, but we can be certain that it was Lee Miller who discovered the effect for herself and Man Ray. Man Ray’s choice of Solarisation as the name of the process suggests he knew something of Sabatier’s experiments, but it was clearly not until Lee Miller’s darkroom accident that he adopted the use of the technique.

In the various interviews she did many years later, Lee claimed she was working in Man Ray’s darkroom developing some negatives when a rat ran over her foot. She screamed and turned on the light. Man Ray immediately turned it off, and in an attempt to save the negative, dumped them in the fixer. To their surprise they found that a clear line surrounded the figure of the nude on the negative. The effect delighted Man Ray who then had to set about learning all he could from this lucky accident so he could replicate it at will. Lee who worked very closely with Man Ray, also used the technique in her own work, which became a hallmark of their artistic association.

No date has ever been established for the first of their solarised works, but it is safe to say it has to have been around 1929 to 1930.

From the way Lee spoke and wrote about the experience of her discovery, it was always easy to assume that the negatives in question were glass plates. Studying Man Ray’s work from that period reveals that he used a predominance of celluloid sheet film, but the solarisation process would have worked equally well on cut sheets of celluloid film.